From the first industrial revolution, technology has been a powerful tool to accelerate growth and improve living standards. But as technology shifts the boundary between the set of tasks performed by humans and those performed by machines, its deployment involves a process of both creation and destruction. Thus, one of the recurrent fears associated with the emergence of “the machine” is the potential to fully replicate human beings’ physical and cognitive capacity, or even surpass it. This, in turn, would leave a significant fraction of workers out of a job and, further, millions of humans struggling to find purpose in a world where work plays such an important role.

Since the last decade, a confluence of a diverse set of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) –with Artificial Intelligence (AI) as the core and general-purpose technology– is again disrupting the world of work, fueling renovated fears of a jobless future among public opinion. The anxiety is particularly strong with AI, given that it has been widely explored and imagined by science fiction well before its implementation as a technology.

Against fears and technological anxieties, a powerful narrative is gaining attention in academic and policy circles around the world.

According to this narrative, both technological developments and demographics trends have paved the way for a new wave of exponential technological change. The future is already here and it is transforming the labor markets through two forces:

First, with new job opportunities, particularly in the set of tasks that complement and augment the power of these technologies.

Second, by threatening jobs that involve tasks that are prone to become obsolete due to the adoption of new technologies.

Both trends would affect entire sectors and jobs throughout the economy but, if history is any guide, the narrative continues, in the long run the positive effect will outweigh the negative impact so that both employment and real wages will increase thanks to technological innovation. The transition from one long-run equilibrium to another takes time and generates various frictions, from widening income inequality to social fragmentation and political backlash. Evidence about these frictions, and policy frameworks to confront and solve them, are already being generated and discussed. Eventually, after a full adjustment of existing curricula to add newly-demanded skills and a reform of the labor markets’ regulatory schemes, a new equilibrium, “new technologies in full use-better jobs,” will be attained.

In a context where the conceptual field is dominated by science fiction, this narrative on the future of work represents a good first step for guiding public policies. A natural next step is to add context and diversity to this narrative. A single and homogeneous narrative on the future of work can hardly account for the real challenges and opportunities facing different countries, let alone the design of its optimal policy frameworks.

Take the Global South. ¿Which are the Global South challenges and opportunities regarding the future of work? To add context and diversity means to engage in a critical appraisal of the global narrative on the future of work based on knowledge and data generated in Global South countries. Luckily, a lot of research has been carried out during the last decade to assess what the future of work is likely to be in the Global South. As a first attempt to systematize this research and data points we have identified five key structural features where the Global South and the Global North differ, and which matter to the future of work. These features are the building blocks that will help us develop a Global South’s own future of work evidence-based narrative.

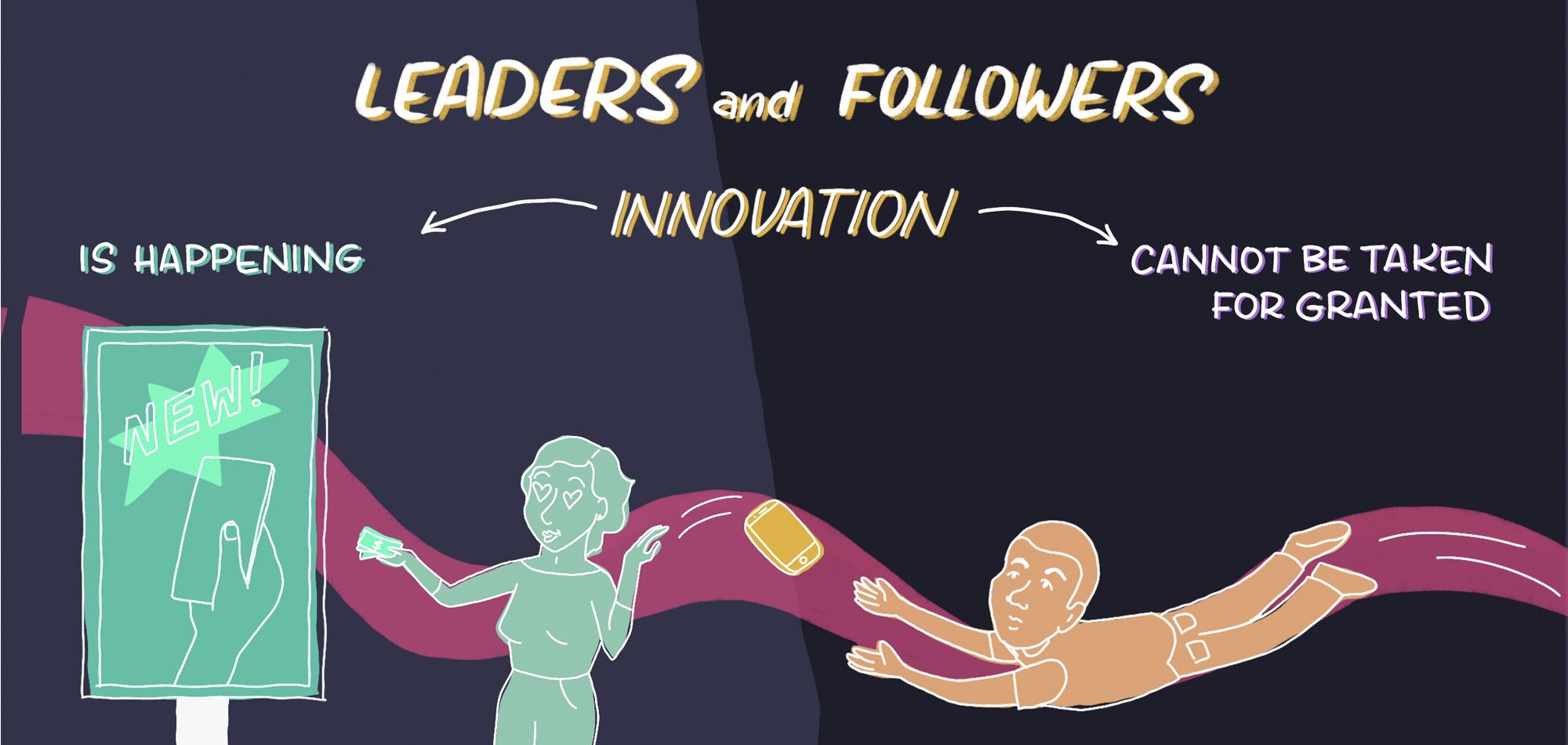

Technology. In terms of technological innovation, the Global South is a follower, not a leader.

Innovation is taking place at accelerated rates in the Global North, but these trajectories cannot be taken for granted in the Global South. Having been “followers” in the previous industrial revolutions, the Global South countries do not necessarily have developed the conditions to innovate systematically or quickly absorb the latest technologies. Innovation is definitely a goal in the Global South, but it needs to be understood and promoted considering the specific contexts and needs of the developing world. Indeed, there is evidence that the pace of technological change is slow in the Global South. Given the Global South’s past trajectories regarding technological change, debates around technology and the future of work should not only be about innovation but also about the adaptation of existing technology and, more generally, about technologies in use. Adaptation matters because novel technologies are being created mainly by the Global North following its own contexts and challenges; the choices about how and when using alien technologies (and how to mix them with local ones) are critical.

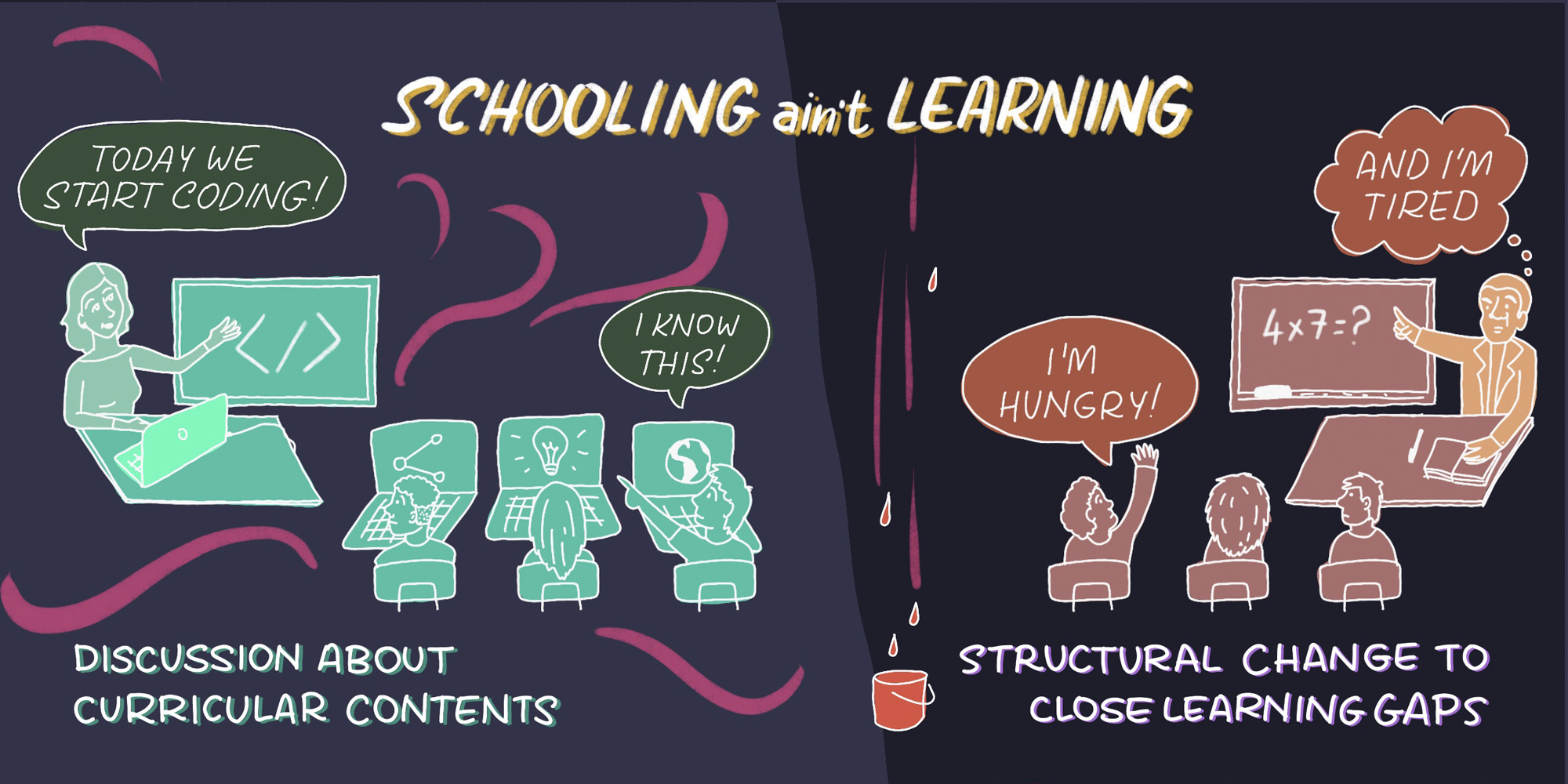

Skills. In the Global South schooling ain’t learning

Adopting the skills relevant to the future in the Global South may require structural improvements in the education systems that go beyond updating curricula. Over the last 50 years, skills development in the Global South has changed drastically. However, neither schooling nor expenditure in education can accurately measure human capital accumulation. When we use these variables as proxies of skills formation, we are assuming that: (a) a year of schooling or a dollar spent on education delivers the same outcome in skills, regardless of the education system; and (b) non-school factors have a negligible effect on education outcomes (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2015). When we analyze actual measures of learning, the outlook is completely different: with some notable exceptions, current skills development systems in developing countries are far from fulfilling their functions (Pritchett, 2013) and reinforce the need for a structural change in the educational system. According to the Programme for International Students Assessment (PISA) conducted by the OECD, average education outcomes in the Global South are falling well behind those obtained in the Global North.

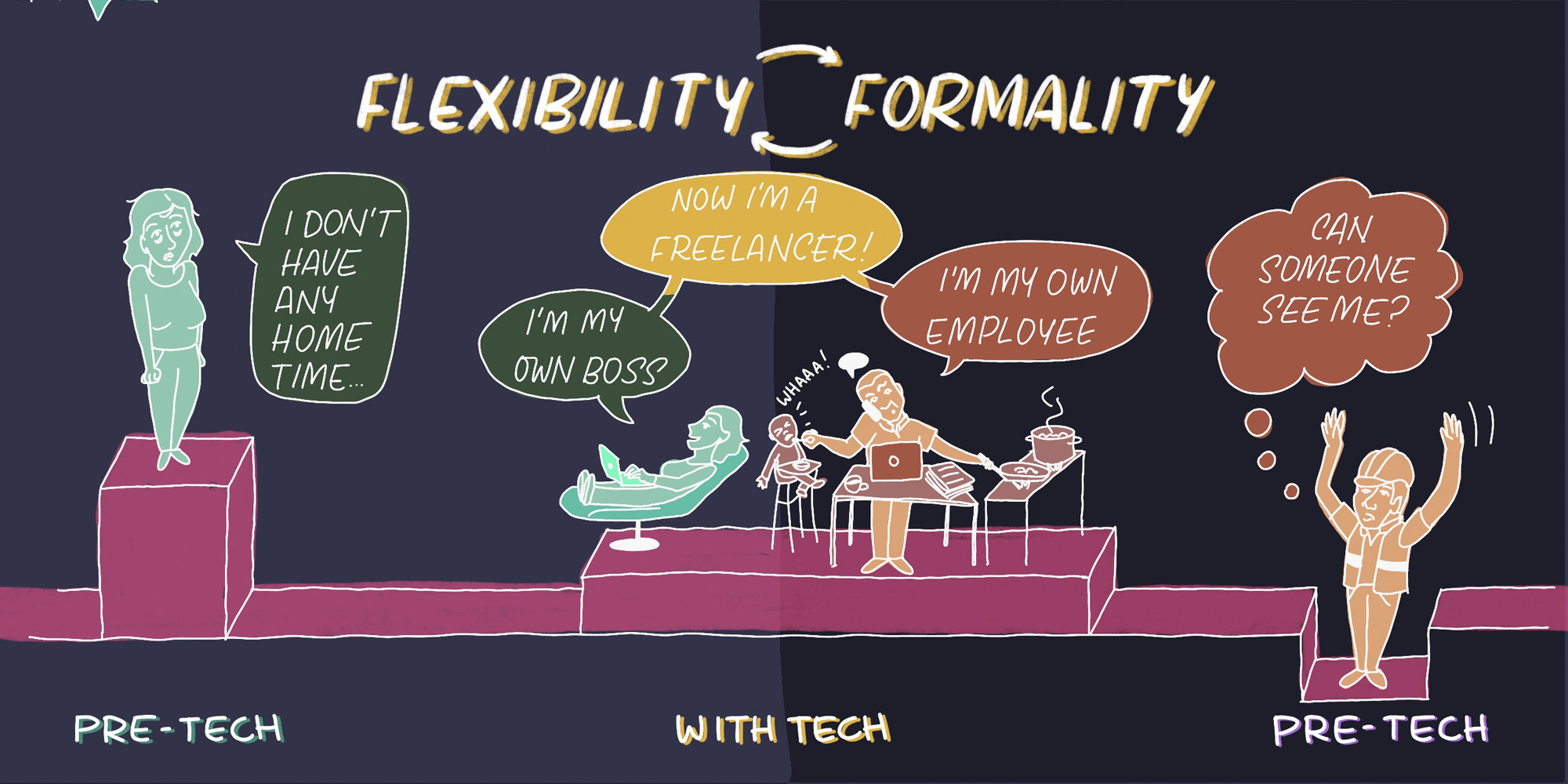

Labor market institutions. While in the Global North technological change may be fostering more flexible and insecure labor markets, in the Global South it creates opportunities as well as challenges

In the Global North, the blurring of firms’ boundaries and the platformization of labor relationships are leading to more flexible labor market settings, where “race to the bottom” dynamics in terms of wages and working conditions are likely to happen. Secure, long-term job positions that characterized what Carles Boix called “Detroit Capitalism” are under threat. But is the Future of Work going to be more flexible and informal? While these threats are present in the Global South, they interact with a variety of opportunities to improve working conditions.

For those working in informal settings – paraphrasing Boix, under “Mumbai Capitalism”- technology can create “entry points” for economic and social policy issues. For those Global South workers with high skills, technology may open a global market to sell high-quality services. In the southern context, technologies such as platforms can operate in the opposite direction: reduce flexibility and informality.

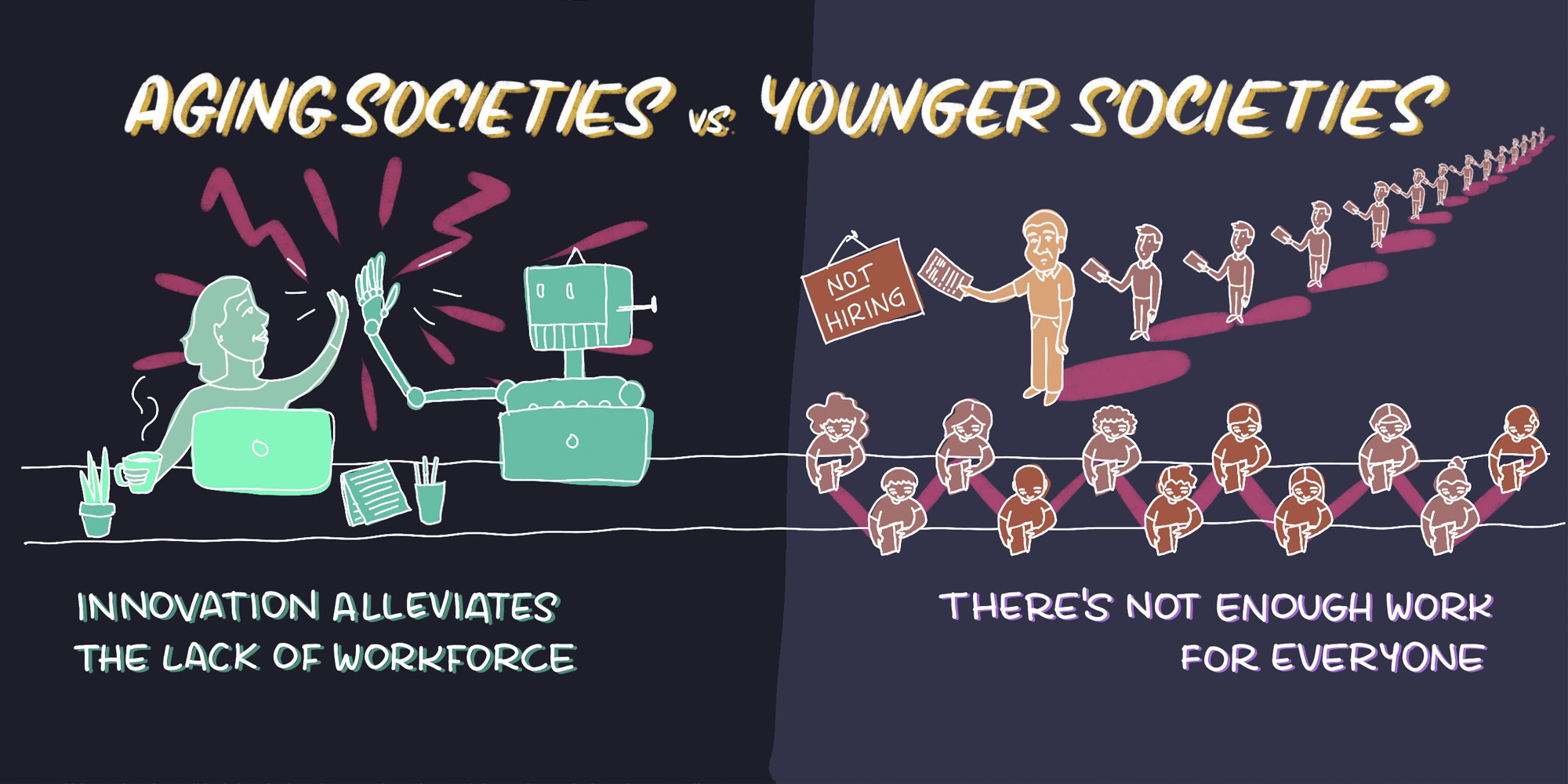

Demography. Demographic asymmetries between the Global North and the Global South matter to the future of work

Although the world is aging, the Global North is older than the Global South. This asymmetry in the stage of the demographic transition implies a different set of challenges regarding the future of work. First, while in the Global North a declining labor force is fueling automation and technological change, in the Global South an ever-expanding working-age population creates huge gaps between the technical feasibility and the economic feasibility of a given innovation. Second, employment creation will be particularly challenging for the Global South, where some 500 million jobs need to be created in the next 2 or 3 decades. Third, the majority of Global South countries are going through the demographic dividend. On this stage, a rising working age population –coupled with big investments in technology and human capital- can become a source of development.

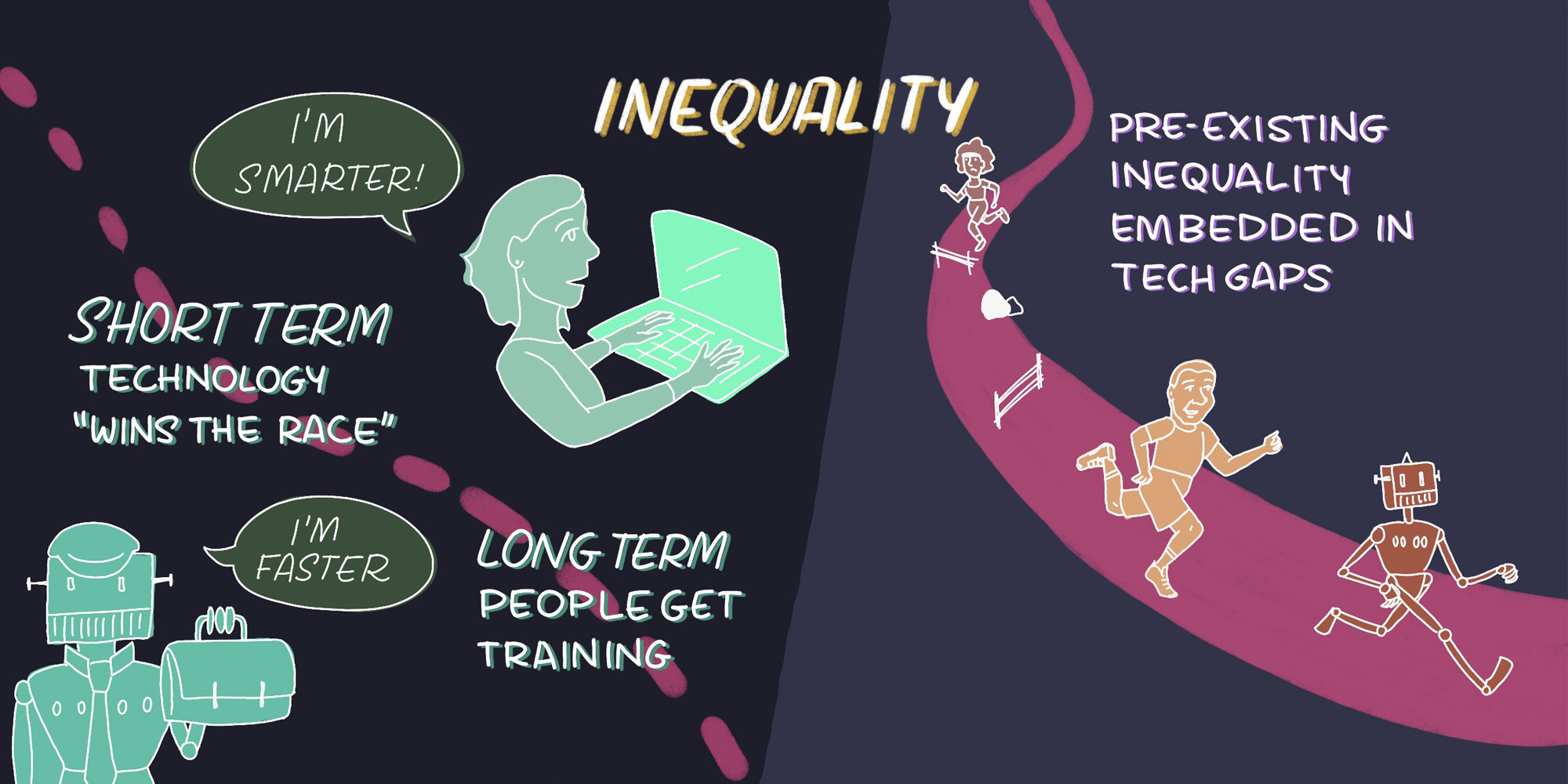

Inequality. While in the Global North economic change is fueling income inequality, in the Global South structural inequality prevents economic change to happen.

In the Global North exponential technological change is feeding income polarization and a hollowing out of the labor market, as middle-skilled, routine jobs are disappearing (see Autor 2010). In the Global South, various sources of structural inequality embedded in wealth, institutions, social norms, and behaviors but visible in the uneven distribution of skills, firms’ capabilities, access to markets, and labor market benefits are preventing exponential technological change from happening.

Will the Future of Work be the same everywhere? History shows that the regions’ idiosyncratic characteristics matter when it comes to technology. Therefore, it is important to keep developing the FoW global narrative to consider the local elements of context that are key for guiding public policy.

There are multiple potential futures for the world of work, and initial conditions are key to determine what policymakers and the private sector need to do to build an inclusive and dynamic one. This calls for more granularity, context and diversity to the global narrative, and for engaging in evidence-based narrative building exercises with a Global South perspective.

The southern perspectives that the FoWiGS network brings to the discussion recognize that there is not a homogeneous Global South. Paraphrasing Leo Tolstoi, each developing country is “underdeveloped” in its own way. Finding the specific building blocks of FoW for Asia, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa is a first step in gaining granularity and help building a better future of work in Global South countries.

IDRC has launched FOWIGS—a research program that will help understand how these changes are affecting the lives of the most vulnerable and suggest pathways for an inclusive digital future. The challenges are large and the questions are complex. But we need to face them now more than ever. Stay connected. Learn how.